Spring is inevitable

the grim certainty of blooming / sorry about the mess & my pamphlet(!) / punctuation in poems / archive intertextuality

Some years ago I went to church with my mum. I am not religious but I was very depressed. The service was about the turning of the seasons, and one line stuck in my head: Spring is inevitable. At the time I liked what I perceived to be its ring of pessimism, a sort of heavy relentlessness which chimed with how I felt. The reminder that every winter is temporary was intended to bring relief, but at that time I was more familiar with dread in response to positive things occurring, since I knew they couldn’t last.

It’s probably ten years or so since that service but around this time of year that line always comes to mind. It’s one lens through which to view the buds, the lambs, March’s tentative fecundity: as both certain and unavoidable. The full phrase was, I believe, we have wintered too long, but Spring is inevitable. Is that right? I remember a we and a but - the collective, the turn. I remember how I felt when I first heard it, my awkwardness at admitting to seeking something from a church service (poor thing!) and how remote that person is now.

A transference of energy. At the moment the year feels like it is spinning and we are grasping onto the edges of things, hoping nothing too important is lost in the whirl of it all. My thoughts appear belatedly, in slivers and glimpses, refusing to coalesce into more than what they first present as. Spring is inevitable: grim certainty that it will surge into being regardless of whether we are ready to receive it.

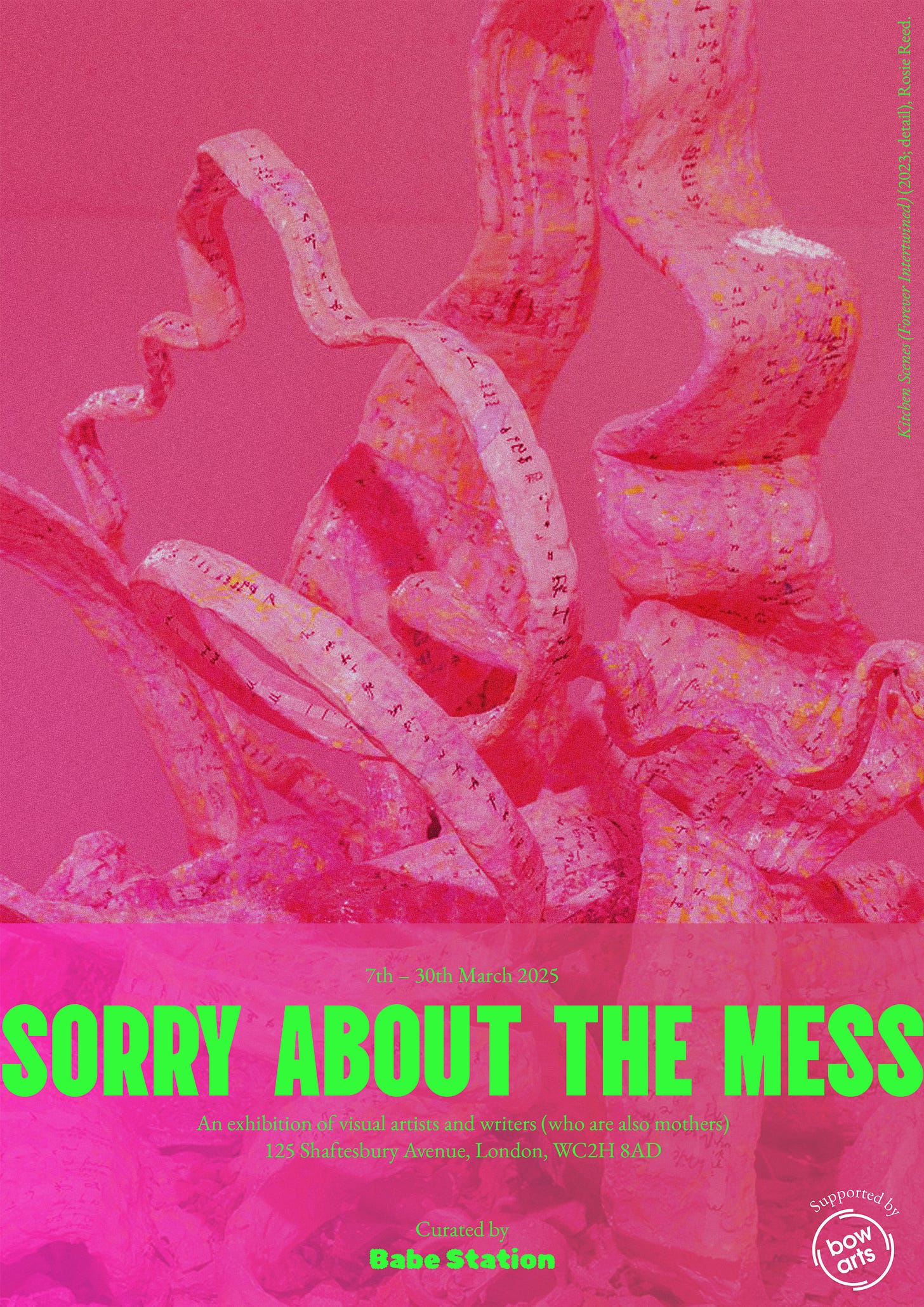

Exciting work things: currently, an exhibition I helped curate (as part of Babe Station) is showing in London, at 125 Shaftesbury Ave (Thurs-Sun 12.30-4.30 ‘til 30 March). The exhibition is called Sorry about the mess and brings together the work of more than 20 artists and writers who are also mothers. In this context mess becomes not just an aesthetic but a condition; an obstacle; a form of critique; a mode of play; a process of creation; an act of revolution.

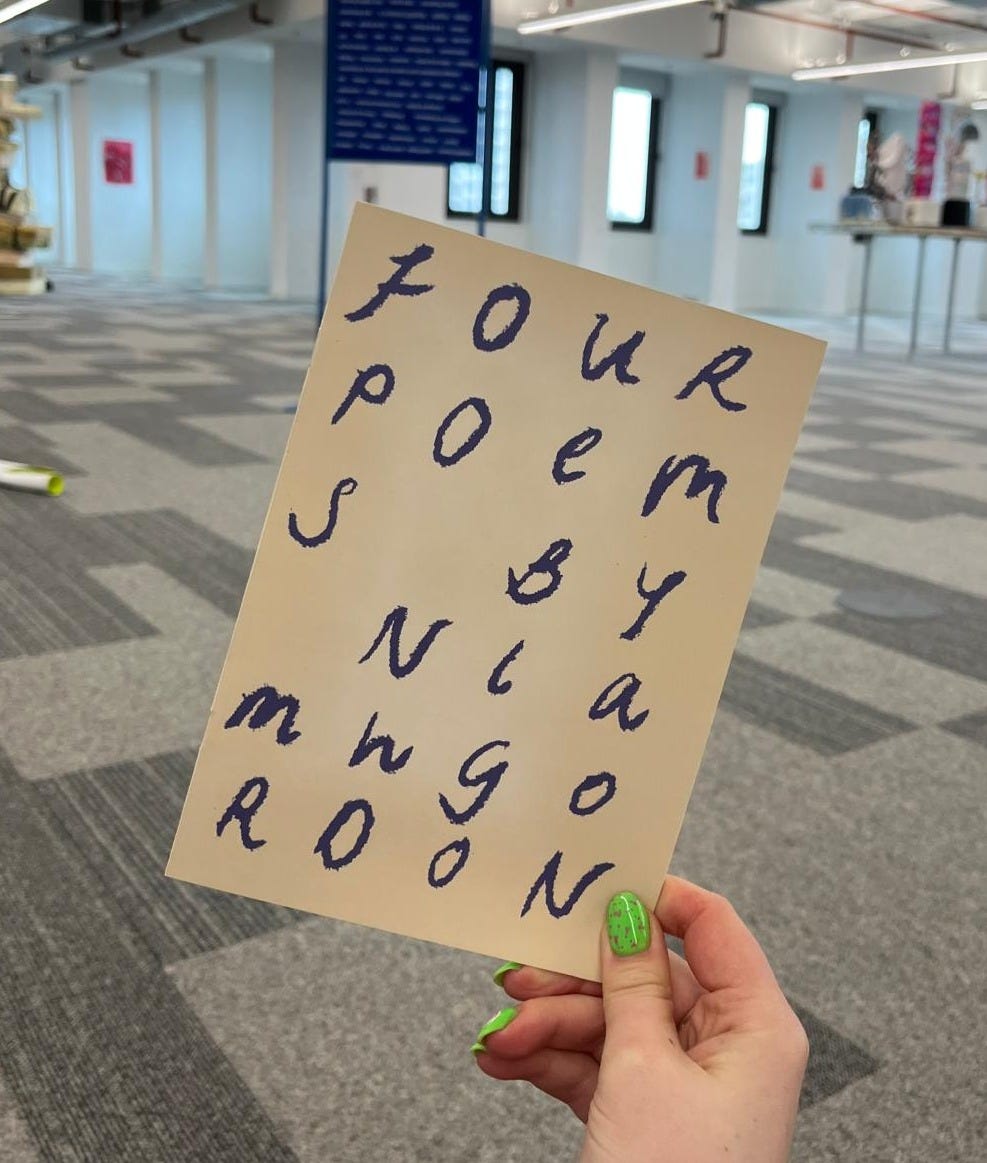

Trebuchet magazine and The Art Newspaper have written about the show, and there’s more info here. This has been a wild, fun experience, my first working with a friend in this way and I have learned a lot. I made a small pamphlet of poems to go with the show which can be purchased here (or you can always email me if you’d like one – can deliver for free in Glasgow!). In the spirit of the exhibition these poems have been amended (edited? played with? drawn on? expanded?) by my daughter whose editions are included alongside plain text versions in the pamphlet.

This semester I’ve been teaching a literature class on writing bodies and illness. One week we looked at a collection of poetry called In Hospital by W. E. Henley. It was written during his confinement in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary between 1873 – 1875, where he received care from the pioneering surgeon Joseph Lister, with the aim of saving his remaining TB-addled foot from amputation. During his treatment Henley wrote a series of poems detailing his experience as a convalescent poet-patient, an educated Englishman in a Scottish hospital for the ill and injured poor. His poems are stark, sometimes unsettling, and notable for their formal experimentation, ranging from sonnets to early examples of free verse. I like ‘Vigil’, about a bad night’s sleep on the ward, in which the speaker describes how his

Shoulders and loins

Ache - - -!

Ache, and the mattress,

Run into boulders and hummocks, […]

In class we discussed this - - - ! and what it generates in the white space of the poem. A bewilderment at pain and its enduring presence alongside desire (those loins), but also a light ridiculousness at any attempt to articulate this conflicting sensation. The stanza continues,

Glows like a kiln, while the bedclothes —

Tumbling, importunate, daft —Ramble and roll […]

Again, I read dark humour in that attempt to describe the tangled sheets. The language grasps for action, shifting to a high poetic register before collapsing into resigned ridicule. And all contained within two dashes, a claustrophobic representation of the sickbed. My favourite part of teaching is probably these moments of close reading in class, when you can observe the poem deconstruct and rearrange itself differently in front of each person.

I’m running again, this time with a goal. A loosely-held training plan which I dare not name in case doing so invokes the series of illnesses which would disrupt and unravel it beyond repair. This weekend I managed my longest run since before I had a baby. Ache - - - ! Legs move of their own accord after a certain point. Earbuds stop working so I run without them. The birdsong is surprisingly deafening and I think where are you all? I can’t see you. An hour ticks by and I’m still going. Not sure what I’m trying to prove.

Where was my body before all this? I try to recover it and find I am lost. It used to terrify me, the idea that you don’t go back to how you were: physically, psychologically, spiritually. But what is this myth of return we’ve been sold? Why would anyone want that? A prelapsarian want: to retreat from hard-won knowledge, instead of acquiescing to it or welcoming it or becoming it.

More busy work things. Thursdays I am at the archive. After dropping O at nursery I take the train into town and walk north, cutting under the motorway and winding along the canal. This week it is bright and clear, frost on the ground and a thin blue sky above. Last week heavy rain and a low grey cloud blocked out the view entirely, but now you can see across the city to the West End, the University spires directing the gaze up and back to the mountains beyond, the Trossachs all green and springy. The canal is still and the sunshine warm. I take the lift up to the fifth floor.

His bookshelves are here ordered as they were. From my seat today I am looking at a collected Dickens, each bound in navy with gold letters. The shelf above is Russian; I see Pushkin, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Chekhov. Above that sits Walter Scott nestled between Byron and James Hogg. Directly in front of me is The Mabinogion, and along this same shelf I can see The Art of Etching, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, The Rise of the Dutch Republic, and then multiple different editions of the collected works of Donne. There is poetry to be found in these juxtaposed titles, which sit on shelves that also house skulls, shells, a pine cone, a model of a Dalek. I find myself idly wondering whether by working here I could osmose this referential corpus.

The archive is an engine of research, engaged in seemingly endless projects which aim to catalogue and arrange Alasdair Gray’s life and works whilst also acting as the creative wellspring from which can be produced brand new writing, new art, new ways of thinking about and understanding Glasgow. Here the project is the city as much as it is the man.

More on the archive next time.